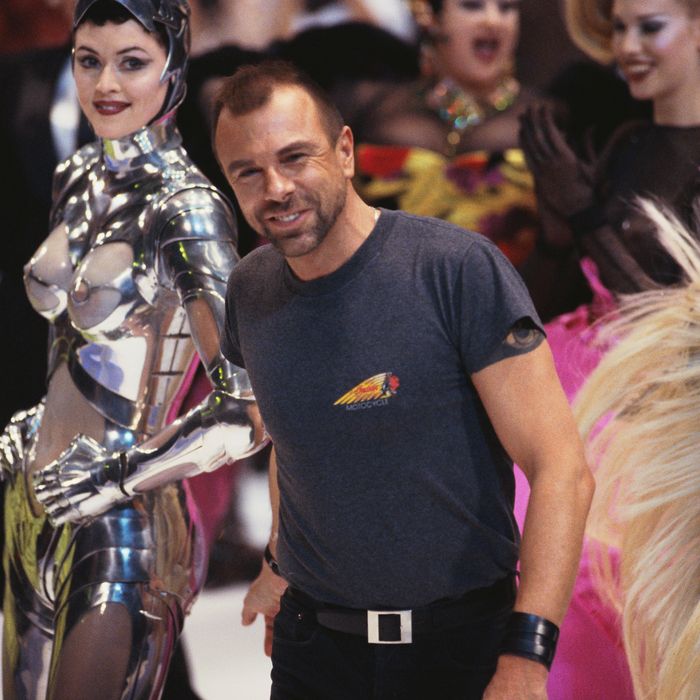

Mugler, center, at his 1995 20th anniversary show.

Photo: Michel Arnaud/Corbis via Getty Images

Even among fashion’s showmen — a dense crowd — one stands alone: Thierry Mugler. Mugler, who died Sunday at 73, was from the ’70s through the ’90s one of the great ringmasters of fashion, an innovator who refused to be limited by the conventions of normal dressing. He did make suits (huge-shouldered ones, the ancestors of the ultrapadded tailoring that’s reliably bubbled back up every few years since) and tight little dresses and swimwear, but he also made robot suits and centurion armor and hand-beaded chaps. “There are two ways you can do fashion shows today,” he once told the New York Times, after a show before 6,000 guests. ”Either you do it very small and private or you do this. I think the public wants it this way.” This way wasn’t in the era of Rihanna streaming the Savage x Fenty runways onto Amazon or the Yeezy show at MSG or Givenchy taking over downtown Manhattan or Chanel sending a rocket ship through the ceiling of the Grand Palais. It was in 1984.

Mugler was a king in ’80s Paris: Alaïa worked for him before opening his own house, and Gaultier was a friend. His shows had been hot tickets for years — “the impossible invitation,” my colleague Cathy Horyn wrote when she first went to Paris to cover the runways in 1987. His work could be wild, inspired by the sex shop or the body shop — like his famous molded motorcycle-grille bustier later worn by Beyoncé, complete with rearview mirrors — but despite his theatrical proclivities, it was not only intended for the stage; when he launched haute couture (nearly a revolution in itself) in 1992, he told the IHT it would be “equally for Madame Mitterrand or Michael Jackson.” (This magazine noted Madame Mitterrand, wife of the French president, front row in 1989, smiling “as models jiggled their assets inches from her nose.”) “If you wanted to become an insect or a superhero or a Hollywood vamp, Mugler was creating the garments to allow you to become whoever you want to be and stage your daily life,” says Thierry-Maxime Loriot, the curator of “Thierry Mugler, Couturissime,” a retrospective of Mugler’s work that began in Montréal (Loriot is from Quebec), traveled to Germany and the Netherlands, and is currently on view at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs. He brought the circus to the runway, and the runway to the circus. His 20th-anniversary show, held at Paris’s Cirque d’Hiver in 1995, was as extravagant as they come, a free-for-all starring Veruschka, Jerry Hall, Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, and, to top it all off, a performance by James Brown.

Photo: Victor VIRGILE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

But the age of mega was waning. “I didn’t feel it at the time, but soon after the show, I realized it was the end of the era,” he said years later. “Afterward, fashion became a branding, marketing thing.” The 1990s saw the rise of corporate fashion, the formation of the luxury groups, the domination of magazines by advertising dollars and advertisers’ demands. A kind of anti-fashion was rising, grungy or minimal rather than voluptuous and maximal: the triumphs of Margiela, Helmut Lang, early Prada. Superheroes were falling out of fashion. Mugler, who had sold his label to the Clarins Group in 1997, exited it in 2002 and devoted himself to stage work, burlesque follies, and the Cirque du Soleil. He also began working with himself as his canvas, changing his once-lithe body — he had trained as a ballet dancer in his youth — into a mass of solid muscle, not far from a superhero himself. He also began going by his given name, Manfred. (Clarins sold the Mugler brand to L’Oréal in 2020.)

It’s tempting to think that — to paraphrase Sunset Boulevard — it wasn’t the artist, but the art that got small, and not just because of the muscle. As Cathy wrote at the Paris unveiling of the “Couturissime” show, while it isn’t fair to compare the fashion world Mugler operated in to the one spinning hecticly today, “despite the perception that fashion is a colossal enterprise … it has actually shrunk as a creative mode of expression.” “He really believed in freedom and not following the trends, the strict rules of couture and the games in the industry,” Loriot says. “That’s why he left the fashion industry in 2002, because it was just not the same anymore. I think he was really misunderstood because he was too much ahead of his time.”

Times always change, and it doesn’t require hand-wringing about fashion today to appreciate Mugler. But it’s certainly true that many of Mugler’s innovations beat his contemporaries and even his successors to the punch. Mugler’s shows were diverse and inclusive long before those were buzzwords: He featured the transgender models Teri Toye and Connie Fleming, the drag artists Joey Arias and Lypsinka, the plus-size model Stella Ellis, and Deee-Lite’s Lady Miss Kier alongside Iman, Naomi, Cindy, Linda, and Christy. “He pushed the envelope,” Arias says, “but he was a perfectionist — to the last detail, even to a quarter-of-an-inch bow on the side of your hip. That bow better be perfect.”

He never fled from pop or pop culture. David Bowie was an early supporter: he wore Mugler womenswear for his 1979 Saturday Night Live performance, with backup from Arias and Klaus Nomi, and later married Iman in a Mugler suit. One of the great runway shows committed to film has got to be the show Mugler magicked up for George Michael’s “Too Funky” video in 1992, starring, among others, Evangelista, Lypsinka, Rossy de Palma, and, again, Arias, who would go on to be a frequent collaborator and friend. (“You are my clay!” Arias remembered Mugler enthusing.) Stadium-size stars have always found in his work a scale to match their own. A new generation of admirers met him on the backs of Lady Gaga, Cardi B, and Kim Kardashian West.

The seven-floor atelier in the Marais where he turned out his creations is no more (it is now, in an ironic reversal, a police station), but the archive endures. (As for the label itself, it continues, currently under the direction of Casey Cadwallader; you may have seen his sinewy, strap-happy designs on FKA twigs. And Angel, the perfume Mugler introduced in 1992, remains a best seller.) “He was misunderstood because of his ideas,” Loriot says, “but also because there was humor. Humor and the fashion industry, sometimes it just doesn’t work, they do not all get irony …” But the last laugh is Manfred’s. The “Couturissime” exhibition is already on the fourth city of its international tour, and when it leaves Paris in April, it might be headed this way. The show goes on.